Riemann–Roch theorem

The Riemann–Roch theorem is an important tool in mathematics, specifically in complex analysis and algebraic geometry, for the computation of the dimension of the space of meromorphic functions with prescribed zeroes and allowed poles. It relates the complex analysis of a connected compact Riemann surface with the surface's purely topological genus g, in a way that can be carried over into purely algebraic settings.

Initially proved as Riemann's inequality by Riemann (1857), the theorem reached its definitive form for Riemann surfaces after work of Riemann's short-lived student Gustav Roch (1865). It was later generalized to algebraic curves, to higher-dimensional varieties and beyond.

Contents |

Motivation

We start with a connected compact Riemann surface of genus g, and a fixed point P on it. We may look at functions having a pole only at P. There is an increasing sequence of vector spaces: functions with no poles (i.e., constant functions), functions allowed at most a simple pole at P, functions allowed at most a double pole at P, a triple pole, ... These spaces are all finite dimensional. In case g = 0 we can see that the sequence of dimensions starts

- 1, 2, 3, ...:

this can be read off from the theory of partial fractions. Conversely if this sequence starts

- 1, 2, ...

then g must be zero (the so-called Riemann sphere).

In the theory of elliptic functions it is shown that for g = 1 this sequence is

- 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ... ;

and this characterises the case g = 1. For g > 2 there is no set initial segment; but it is possible to say what the tail of the sequence must be. It is also possible to explain why the case g = 2 is somewhat special, by means of the theory of hyperelliptic curves, namely those with the sequence starting 1, 1, 2, ... .

The reason that the results take the form they do goes back to the formulation (Roch's part) of the theorem: as a difference of two such dimensions. When one of those can be set to zero, we get an exact formula, which is linear in the genus and the degree (i.e. number of degrees of freedom). Already the examples given allow a reconstruction in the shape

- dimension − correction = degree − g + 1.

For g = 1 the correction is 1 for degree 0; and otherwise 0. The full theorem explains the correction as the dimension associated to a further, 'complementary' space of functions.

Statement of the theorem

In now-accepted notation, the statement of Riemann–Roch for a compact Riemann surface of genus g with canonical divisor K is

- l(D) − l(K − D) = deg(D) − g + 1.

This applies to all divisors D, elements of the free abelian group on the points of the surface. Equivalently, a divisor is a finite linear combination of points of the surface with integer coefficients.

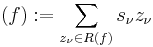

We define the divisor of a meromorphic function f as

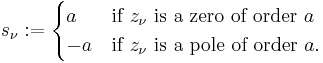

where R(f) is the set of all zeroes and poles of f, and sν is given by

We define the divisor of a meromorphic 1-form similarly. A divisor of a global meromorphic function is called a principal divisor. Two divisors that differ by a principal divisor are called linearly equivalent. A divisor of a global meromorphic 1-form is called the canonical divisor (usually denoted K). Any two meromorphic 1-forms will yield linearly equivalent divisors, so the canonical divisor is uniquely determined up to linear equivalence (hence "the" canonical divisor).

The symbol deg(D) denotes the degree of the divisor D, i.e. the sum of the coefficients occurring in D. It can be shown that the divisor of a global meromorphic function always has degree 0, so the degree of the divisor depends only on the linear equivalence class.

The number l(D) is the quantity that is of primary interest: the dimension (over C) of the vector space of meromorphic functions h on the surface, such that all the coefficients of (h) + D are non-negative. Intuitively, we can think of this as being all meromorphic functions whose poles at every point are no worse than the corresponding coefficient in D; if the coefficient in D at z is negative, then we require that h has a zero of at least that multiplicity at z – if the coefficient in D is positive, h can have a pole of at most that order. The vector spaces for linearly equivalent divisors are naturally isomorphic through multiplication with the global meromorphic function (which is well-defined up to a scalar).

Even if we don't know anything about K, we know at least that the index of speciality[1][2] (the "correction" referred to above) is non-negative, so that

- l(K − D) ≥ 0,

and therefore

- l(D) ≥ deg(D) − g + 1

which is Riemann's inequality mentioned earlier.

The theorem above is correct for all compact connected Riemann surfaces. The formula also holds for all non-singular projective algebraic curves over an algebraically closed field k. Here l(D) denotes the dimension (over k) of the space of rational functions on the curve whose poles at every point are not worse than the corresponding coefficient in D.

To relate this to our example above, we need some information about K: for g = 1 we can take K = 0, while for g = 0 we can take K = −2P (any P). In general K has degree 2g − 2. As long as D has degree at least 2g − 1 we can be sure that the correction term is 0.

Going back therefore to the case g = 2 we see that the sequence mentioned above is

- 1, 1, ?, 2, 3, ... .

It is shown from this that the ? term of degree 2 is either 1 or 2, of course depending on the point. It can be proven that in any genus 2 curve there are exactly six points whose sequences are 1, 1, 2, 2, ... and the rest of the points have the generic sequence 1, 1, 1, 2, ... In particular, a genus 2 curve is a hyperelliptic curve. For g > 2 it is always true that at most points the sequence starts with g+1 ones and there are finitely many points with other sequences (see Weierstrass points).

Riemann-Roch for Line Bundles

Let L be a holomorphic line bundle on a compact Riemann surface X of genus g and let  denote the space of holomorphic sections of L. This space will be finite-dimensional; its dimension is denoted

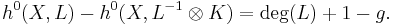

denote the space of holomorphic sections of L. This space will be finite-dimensional; its dimension is denoted  . Let K denote the canonical bundle on X. Then, the Riemann-Roch theorem states that

. Let K denote the canonical bundle on X. Then, the Riemann-Roch theorem states that

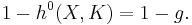

The theorem of the previous section is the special case of when L is a point bundle. The theorem can be applied to show that there are g holomorphic sections of K, or one-forms, on X. Taking L to be the trivial bundle,  since the only holomorphic functions on X are constants. The degree of L is zero, and L^{-1} is the trivial bundle. Thus,

since the only holomorphic functions on X are constants. The degree of L is zero, and L^{-1} is the trivial bundle. Thus,

Therefore,  , proving that there are g holomorphic one-forms.

, proving that there are g holomorphic one-forms.

Generalizations of the Riemann-Roch Theorem

The Riemann–Roch theorem for curves was proved for Riemann surfaces by Riemann and Roch in the 1850s and for algebraic curves by F. K. Schmidt in 1929 (cf. the dedicated article Riemann-Roch theorem for algebraic curves). It is foundational in the sense that the subsequent theory for curves tries to refine the information it yields (for example in the Brill–Noether theory).

There are versions in higher dimensions (for the appropriate notion of divisor, or line bundle). Their general formulation depends on splitting the theorem into two parts. One, which would now be called Serre duality, interprets the l(K − D) term as a dimension of a first sheaf cohomology group; with l(D) the dimension of a zeroth cohomology group, or space of sections, the left-hand side of the theorem becomes an Euler characteristic, and the right-hand side a computation of it as a degree corrected according to the topology of the Riemann surface.

In algebraic geometry of dimension two such a formula was found by the geometers of the Italian school; a Riemann–Roch theorem for algebraic surfaces was proved (there are several versions, with the first possibly being due to Max Noether). So matters rested before about 1950.

An n-dimensional generalisation, the Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem, was found and proved by Friedrich Hirzebruch, as an application of characteristic classes in algebraic topology; he was much influenced by the work of Kunihiko Kodaira. At about the same time Jean-Pierre Serre was giving the general form of Serre duality, as we now know it.

Alexander Grothendieck proved a far-reaching generalization in 1957, now known as the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem. His work reinterprets Riemann–Roch not as a theorem about a variety, but about a morphism between two varieties. The details of the proofs were published by Borel-Serre in 1958.

Finally a general version was found in algebraic topology, too. These developments were essentially all carried out between 1950 and 1960. After that the Atiyah–Singer index theorem opened another route to generalization.

What results is that the Euler characteristic (of a coherent sheaf) is something reasonably computable. If one is interested, as is usually the case, in just one summand within the alternating sum, further arguments such as vanishing theorems must be brought to bear.

Notes

References

- Borel, Armand & Serre, Jean-Pierre (1958), Le théorème de Riemann-Roch, d'après Grothendieck, Bull.S.M.F. 86 (1958), 97-136.

- Grothendieck, Alexander, et al. (1966/67), Théorie des Intersections et Théorème de Riemann-Roch (SGA 6), LNM 225, Springer-Verlag, 1971.

- William Fulton (1974). Algebraic Curves. Mathematics Lecture Note Series. W.A. Benjamin. ISBN 0-8053-3081-4., available online at [1]

- Jost, Jürgen (2006). Compact Riemann Surfaces. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-33065-3, see pages 208–219 for the proof in the complex situation. Note that Jost uses slightly different notation.

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977). Algebraic Geometry. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9. OCLC 13348052. MR0463157, contains the statement for curves over an algebraically closed field. See section IV.1.

- Hirzebruch, Friedrich (1995). Topological methods in algebraic geometry. Classics in Mathematics. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-58663-0. MR1335917. A good general modern reference.

- Shigeru Mukai; William Oxbury (translator) (2003). An Introduction to Invariants and Moduli. Cambridge studies in advanced mathematics. 81. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80906-1.

- Riemann, Bernhard (1857). "Theorie der Abel'schen Functionen". Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 54: 115–155. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN243919689_0054

- Roch (1865). "Ueber die Anzahl der willkurlichen Constanten in algebraischen Functionen". Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 64: 372–376. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN243919689_0064

- Henning Stichtenoth (1993). Algebraic Function Fields and Codes. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-56489-6.

- Misha Kapovich, The Riemann–Roch Theorem (lecture note) an elementary introduction

- J. Gray, The Riemann-Roch theorem and Geometry, 1854-1914.